Picasso. La muchacha de los pies descalzos. Musée Picasso,París. © Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2015. © RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau / Adrien Didierjean

|

|

|

|

OS BIOGRAPHY |

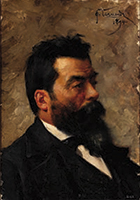

HIS TEACHERS |

A CORUÑA 1891–1895 |

A CORUÑA TODAY |

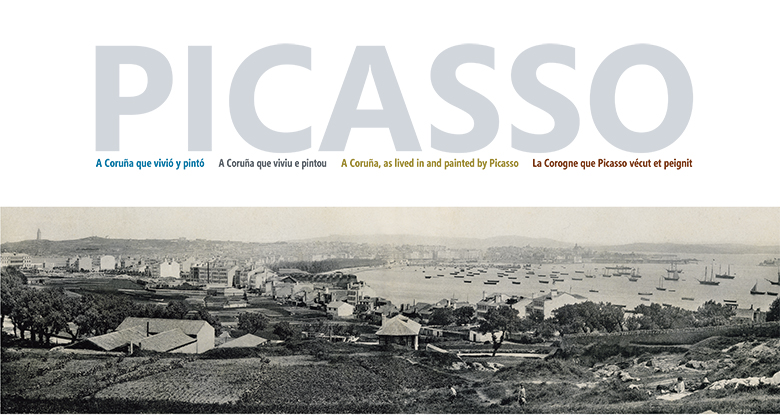

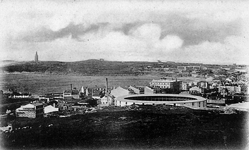

The city of A Coruña that Picasso knew was a thriving city experiencing rapid growth. With almost 40,000 inhabitants, it had become the most populous city in Galicia. By mid-century, the city walls surrounding what nowadays is the old town, the city centre, were demolished in order to easily connect Pescadería and encourage the city's development. By the eighties the expansion district was already being designed. In this new area, which was still under construction at the time, the Ruiz Picasso family set up their home in a rented apartment on Payo Gómez Street in 1891.

The old town was mainly occupied by religious and military buildings, whereas the Pescadería was destined to house families, factories and shops. The area around María Pita had been cleared, although its configuration back then was very different from its current appearance, with barely a dozen houses built. The City Council was located in the former Saint Augustin's convent, which was annexed to Saint George's church before it moved to Franja Street.

Pescadería's name is not a coincidence. It is located on a small isthmus between the two seas: the windy Orzán and the more protected Marina. Most of the activities that took place there were related to fishery.

The Marina galleries were almost entirely finished when the Ruiz Picasso family arrived in A Coruña. Installing galleries in houses was a common practice in the city that began in mid-century and also happened in Betanzos, Pontedeume and Ferrol. Payo Gómez's house also had galleries. They were fixed in Picasso's memory and many years later he would ask his friend, the journalist Olano, about them.

Real and San Andrés streets connected the old town to the city's access points. They were also two important commercial streets where some of the most famous cafés, such as Suizo, Café de Puga, Universal or Café Restaurant stood. The main shops were there too, and they offered all kinds of new and assorted merchandising. There were, among others, Farmacia Villar, Fotografía Sellier, Papelería de Ferrer, Canuto Berea's music shop or Carré Aldao's Librería Regional. Back then it was common for local painters to exhibit their works in shop windows on Real Street in hopes of selling them. It was not only something that students such as young Picasso would do, but also more established painters such as José Ruiz Blasco, Picasso's father, or Román Navarro, both professors at the Fine Arts school.

Busy market stalls were set up in the Lugo, Santa Catalina and San Agustín squares, since there was not yet a building designated to house the market. Most of the groceries sold there, especially the fruits and vegetables, came from the nearby district of Oza. The coastal-fishing also came from nearby villages.

Goods used to be carried in baskets on someone's head or in carts pulled by animals. People used to walk by foot or in carts pulled by horses or oxen. Although some other cities had streetcars pulled by mules, they would not be used in A Coruña until some years later. Back then A Coruña was a small city, its municipality, not reaching 8 km2, was the smallest of the whole province.

Pasaje Bridge was not yet built, but there were steamships and boats crossing the bay towards Santa Cristina, Santa Cruz and Mera.

There was a bus service that connected to nearby villages. Some of them, such as the carrilana from Santiago, had their stop at the Obelisco district, an area with many lodges and inns. It would still be a few years before the mule-pulled streetcars or the first motor vehicles were used in the city.

It is important to bear in mind that in 1850 the journey by road between A Coruña and Madrid took five and a half days, so it is easy to understand that any improvement in the precarious transportation network would have been enthusiastically received. Despite the improvements, journeys were still long, difficult and often risky.

The activity in the port played an important role in the expansion of the city. The traffic of passengers and goods to other places within the peninsula, Europe, America and the Philippines was intense. The Ruiz Picasso family travelled by ship from Málaga experiencing a journey, according to Picasso's biographers, so awful that they decided to land at Vigo and continue their journey by land. They most likely had been afraid, due to the incident one year prior, of the sinking of the British Royal Navy ship HMS Serpent in Camariñas where 172 people perished. A commemorative stone plaque still stands in the San Carlos park to honour the dead.

The railway network connecting to Madrid, inaugurated by King Alfonso XII and Queen María Cristina in 1883, managed to promote the port's appeal and the distribution of local goods to the capital. The railway station was located in A Gaiteira, quite a distance from the city centre, according to the concept of distances back then. It stayed there until the 1960s.

Despite the small stature of the Obelisk by today’s standards, back then it stood-out as one of the tallest buildings in the city, as the tallest buildings were only three to four storeys high. The Teatro Linares Rivas, located where some years later the Cine Avenida would stand, and the Banco Pastor building, the tallest building in Spain when it was completed, had not yet been constructed.

Pasaje Bridge was not yet built, but there were steamships and boats crossing the bay towards Santa Cristina, Santa Cruz and Mera.

There was a bus service that connected to nearby villages. Some of them, such as the carrilana from Santiago, had their stop at the Obelisco district, an area with many lodges and inns. It would still be a few years before the mule-pulled streetcars or the first motor vehicles were used in the city.

It is important to bear in mind that in 1850 the journey by road between A Coruña and Madrid took five and a half days, so it is easy to understand that any improvement in the precarious transportation network would have been enthusiastically received. Despite the improvements, journeys were still long, difficult and often risky.

The activity in the port played an important role in the expansion of the city. The traffic of passengers and goods to other places within the peninsula, Europe, America and the Philippines was intense. The Ruiz Picasso family travelled by ship from Málaga experiencing a journey, according to Picasso's biographers, so awful that they decided to land at Vigo and continue their journey by land. They most likely had been afraid, due to the incident one year prior, of the sinking of the British Royal Navy ship HMS Serpent in Camariñas where 172 people perished. A commemorative stone plaque still stands in the San Carlos park to honour the dead.

The railway network connecting to Madrid, inaugurated by King Alfonso XII and Queen María Cristina in 1883, managed to promote the port's appeal and the distribution of local goods to the capital. The railway station was located in A Gaiteira, quite a distance from the city centre, according to the concept of distances back then. It stayed there until the 1960s.

Despite the small stature of the Obelisk by today’s standards, back then it stood-out as one of the tallest buildings in the city, as the tallest buildings were only three to four storeys high. The Teatro Linares Rivas, located where some years later the Cine Avenida would stand, and the Banco Pastor building, the tallest building in Spain when it was completed, had not yet been constructed.

With no traffic jams, the Cantón was extraordinarily wide, landscaped, and with many rows of trees and benches. Thanks to private donations from some wealthy patrons and public underwriting, a huge area had been opened up to the sea, and Méndez Núñez Park was established there. Until then, the only park in the city was San Carlos, located in the old town, one of Picasso's favourite spots, since he was fascinated with the story of Sir John Moore and his supposed lover Lady Hester Stanhope. Méndez Núñez immediately became one of the locals' favourite walks. It had gas-lightning, rental chairs, a music kiosk, and small theatres and performances could often be enjoyed there. The Ruiz Picasso family used to walk along these new park next to their home.

One of the places where Picasso spent a lot of time was Pontevedra Square. This was not only because the school was there, but also because it was the perfect place to play with his friends away from his mother's sight. It was a very wide square, with plenty of trees and open to the sea. There was a drinking fountain and a public washing place which were very useful to the community at the time.

One of the places where Picasso spent a lot of time was Pontevedra Square. This was not only because the school was there, but also because it was the perfect place to play with his friends away from his mother's sight. It was a very wide square, with plenty of trees and open to the sea. There was a drinking fountain and a public washing place which were very useful to the community at the time.

Apart from very few exceptions, such as the Farmacia Villar, with its own well, Pérez Costales' home, or Eusebio da Guarda High School, houses generally did not have running water. People were forced to collect their water daily in the most common recipients called sellas from public drinking fountains, this was a tough chore and was assigned to the women who were in charge of all domestic duties. Women and even girls used to work as laundry women, servants and errand girls in exchange for meagre wages, and sometimes with no payment more than a meal.

The water came from San Pedro de Visma and Vioño and was channelled to the drinking fountains and washing places of the city (even places as distant as Azcárraga Square) through a rudimentary system of channels and traps. In the Bridges Promenade, the former Carballo Square, the aqueduct used back then still stands. Until the 20th century there was not a modern water supply system in the city.

The problems with the supply of water and poor levels of hygiene caused typhus and many other contagious disease outbreaks, which in addition to a nutrient deficient diet and a lack of healthcare, illnesses such as the flu or gastroenteritis were very serious and even deadly. As a result, in 1893 a doctor from Lugo identified cafés to be the focal points of these diseases due to their dirty latrines, crockery and cutlery. They also served low-quality alcohol, and their clients were constantly exposed to tobacco smoke and the residue from gas-lighting. The death of Conchita, Picasso's youngest sister, was due to diphtheria and came as a shock for the family, but if we take into account that the child mortality rate was around 200 out of every 1,000 children, it was not an extraordinary event.

The streets were not as clean as they should have been and there were frequent complaints due to foul odours. There were public announcements encouraging improvements in personal hygiene, the boiling of drinking water and the throwing of lime into toilets. The municipal heater was also available for the community in order to be used to disinfect the clothes of the sick and the deceased in order to avoid contagious diseases.

The water came from San Pedro de Visma and Vioño and was channelled to the drinking fountains and washing places of the city (even places as distant as Azcárraga Square) through a rudimentary system of channels and traps. In the Bridges Promenade, the former Carballo Square, the aqueduct used back then still stands. Until the 20th century there was not a modern water supply system in the city.

The problems with the supply of water and poor levels of hygiene caused typhus and many other contagious disease outbreaks, which in addition to a nutrient deficient diet and a lack of healthcare, illnesses such as the flu or gastroenteritis were very serious and even deadly. As a result, in 1893 a doctor from Lugo identified cafés to be the focal points of these diseases due to their dirty latrines, crockery and cutlery. They also served low-quality alcohol, and their clients were constantly exposed to tobacco smoke and the residue from gas-lighting. The death of Conchita, Picasso's youngest sister, was due to diphtheria and came as a shock for the family, but if we take into account that the child mortality rate was around 200 out of every 1,000 children, it was not an extraordinary event.

The streets were not as clean as they should have been and there were frequent complaints due to foul odours. There were public announcements encouraging improvements in personal hygiene, the boiling of drinking water and the throwing of lime into toilets. The municipal heater was also available for the community in order to be used to disinfect the clothes of the sick and the deceased in order to avoid contagious diseases.

A Coruña had the Hospital de la Caridad, the first hospital built in the city, founded by Teresa Herrera in 1794 and the Hospital Militar del Buen Suceso, which is the current Hospital Abente y Lago, but it lacked a public health system so that was partly made up for by charity programs. The recently founded Red Cross had little time to rest after its foundation in 1864, a few years later the city was devastated by cholera and plague outbreaks.

The construction of the Lazareto de Oza (1889), where travellers from countries with epidemic diseases were kept in quarantine, was an important breakthrough. Apart from being a service for the city, its existence was a competitive advantage for the port, because it allowed the reception of ships from a larger number of countries.

The construction of the Lazareto de Oza (1889), where travellers from countries with epidemic diseases were kept in quarantine, was an important breakthrough. Apart from being a service for the city, its existence was a competitive advantage for the port, because it allowed the reception of ships from a larger number of countries.

When A Coruña was designated as the capital of the province within the Spanish administrative reorganisation in 1883, the city benefited from a business point of view. Many companies set up their headquarters in the city, even though their main activities were developed elsewhere within the provincial territory.

By mid-century the Banco de La Coruña was founded and it issued money until 1875, when a branch office of the Banco de España was settled in the city and was appointed exclusively to that activity. The growth of the city during those years could be concluded from the foundation of the Banco de Crédito Gallego and the Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad.

The most important industry in the city was the Fábrica de Tabacos, located in A Palloza, back then a rural area in the outskirts, hiring four thousand working women and a large number of working men in 1890.

The production of glass was also noteworthy. The most important factory was La Coruñesa, with more than two hundred workers. There were also La Protegida and La Esperanza Coruñesa. As an interesting fact, the Cristales district was named after a former glass factory.

Textile production was also important. La Primera Coruñesa, on Camino Nuevo, the now Juan Flórez Street, was the first one of its kind in the city in 1874. More than two hundred people used to work there, most of them women.

The hat business had also been booming in the city from the beginning of the century. At that time, both men and women used to wear hats. Large productions of hats were churned out at the factory at Estrecha de San Andrés, and they became very famous throughout Spain for the quality of their hats. They were the providers for the Royal Household. It was owned by Pedro Barrié, Barrié de la Maza's uncle.

Many everyday items were also produced in the city. There were gas production factories for the public lightning supplying. Soap, flour, and pasta for soup were also products made in A Coruña. Fish-salting and canning industries were important as well; they were located next to Palloza harbour.

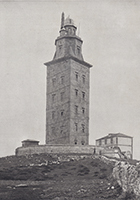

There were some distilleries, soda factories and breweries, the latter was a beverage yet to be popular. La Torre de Hércules and Merckel were some of the beer brands produced in A Coruña at that time.

There were also several chocolate factories, a very popular product in the city, specially infused cocoa shells. They were so popular that people from A Coruña were colloquially and intentionally called cascarilleiros (cocoa shell consumers). One of the reasons why this product was so popular was probably due to its low price which was even cheaper than coffee and chocolate.

By mid-century the Banco de La Coruña was founded and it issued money until 1875, when a branch office of the Banco de España was settled in the city and was appointed exclusively to that activity. The growth of the city during those years could be concluded from the foundation of the Banco de Crédito Gallego and the Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad.

The most important industry in the city was the Fábrica de Tabacos, located in A Palloza, back then a rural area in the outskirts, hiring four thousand working women and a large number of working men in 1890.

The production of glass was also noteworthy. The most important factory was La Coruñesa, with more than two hundred workers. There were also La Protegida and La Esperanza Coruñesa. As an interesting fact, the Cristales district was named after a former glass factory.

Textile production was also important. La Primera Coruñesa, on Camino Nuevo, the now Juan Flórez Street, was the first one of its kind in the city in 1874. More than two hundred people used to work there, most of them women.

The hat business had also been booming in the city from the beginning of the century. At that time, both men and women used to wear hats. Large productions of hats were churned out at the factory at Estrecha de San Andrés, and they became very famous throughout Spain for the quality of their hats. They were the providers for the Royal Household. It was owned by Pedro Barrié, Barrié de la Maza's uncle.

Many everyday items were also produced in the city. There were gas production factories for the public lightning supplying. Soap, flour, and pasta for soup were also products made in A Coruña. Fish-salting and canning industries were important as well; they were located next to Palloza harbour.

There were some distilleries, soda factories and breweries, the latter was a beverage yet to be popular. La Torre de Hércules and Merckel were some of the beer brands produced in A Coruña at that time.

There were also several chocolate factories, a very popular product in the city, specially infused cocoa shells. They were so popular that people from A Coruña were colloquially and intentionally called cascarilleiros (cocoa shell consumers). One of the reasons why this product was so popular was probably due to its low price which was even cheaper than coffee and chocolate.

City councils, and A Coruña was no exception, did not usually have enough income in their budgets which was mainly obtained from taxes on commercial activities. As a result, the services they could provide were reduced and deficient, and municipal workers were poorly paid.

Services that required expensive infrastructure, such as electricity, gas, or transportation, were usually managed by private companies. City councils would only directly assume the most basic services, such as cleaning, cemeteries or markets. The income derived from the activities at municipal theatres was allocated to charities.

The construction of some buildings and monuments was made possible thanks to private donations from some wealthy patrons and public underwriting. The Teatro Principal, a part of Méndez Núñez Park, and the Obelisk were built from these contributions. Eusebio da Guarda took on the the payment for the construction of San Andrés chapel, the high school, the schools and the market in Lugo Square. Picasso's father donated one peseta for the monument to Daniel Carballo in the new land extension.

During the years Picasso lived in A Coruña, the mayors were Antonio Pérez Dávila, José Soto, José Marchesi Dalmau, Enrique Fernández Herce and Carlos Martínez Esparís. Marchesi promoted urban development and he was responsible for María Pita Square and the introduction of the electrical grid in the city.

The lightning system, both public and domestic, was based on gas and as a result outbreaks of fires were frequent. By the end of the century the electrical system was introduced. The Teatro Principal, which was rebuilt after a fire, was the first building with electrical lightning.

There were no telephones in houses. In 1888 the first hand-controlled switchboard was established in the city and from that point onward more and more were installed, however all of them were private, since there was no public telephone network.

However, the city offered a certain number of services and comforts and was well-known for its leisure activities.

Services that required expensive infrastructure, such as electricity, gas, or transportation, were usually managed by private companies. City councils would only directly assume the most basic services, such as cleaning, cemeteries or markets. The income derived from the activities at municipal theatres was allocated to charities.

The construction of some buildings and monuments was made possible thanks to private donations from some wealthy patrons and public underwriting. The Teatro Principal, a part of Méndez Núñez Park, and the Obelisk were built from these contributions. Eusebio da Guarda took on the the payment for the construction of San Andrés chapel, the high school, the schools and the market in Lugo Square. Picasso's father donated one peseta for the monument to Daniel Carballo in the new land extension.

During the years Picasso lived in A Coruña, the mayors were Antonio Pérez Dávila, José Soto, José Marchesi Dalmau, Enrique Fernández Herce and Carlos Martínez Esparís. Marchesi promoted urban development and he was responsible for María Pita Square and the introduction of the electrical grid in the city.

The lightning system, both public and domestic, was based on gas and as a result outbreaks of fires were frequent. By the end of the century the electrical system was introduced. The Teatro Principal, which was rebuilt after a fire, was the first building with electrical lightning.

There were no telephones in houses. In 1888 the first hand-controlled switchboard was established in the city and from that point onward more and more were installed, however all of them were private, since there was no public telephone network.

However, the city offered a certain number of services and comforts and was well-known for its leisure activities.

Following the trends set in other coastal cities, the construction was beginning on what would become precursors to today's current health resorts. Riazor had the Casa de Baños de Mar Calientes, a pioneer in the use of showers, which was not very common back then. In Rubine, near the Ruiz Picasso house, you could find the La Salud and La Primitiva. Whereas some of these spas were humble, some others were luxurious and comfortable resorts that offered all kinds of services, such as free medical visits, health treatments, gyms, fencing rooms, reading rooms, or piano rooms. The Balneario de la Beneficencia Municipal was not likely to provide so many amenities.

The Balneario de Arteixo was a highly regarded, relaxing resort. The habit of spending the summer away from home was becoming popular among the upper classes. Those who could afford it used to visit these places.

The Balneario de Arteixo was a highly regarded, relaxing resort. The habit of spending the summer away from home was becoming popular among the upper classes. Those who could afford it used to visit these places.

At that time, bathing in the sea was considered more of a health related activity than a leisure activity and many who took baths did so following their doctor's orders. Some others used to walk along the beach, all dressed up.

The locals' favourite beach was Riazor: it was sheltered, its sand was fine and clean, and there were designated changing room cabins. People were forced to use these since it was forbidden to change clothes outdoors. Riazor offered plenty of services: there were inns, lifeguard boats and ropes that stretched far out into the sea so that swimmers could hold onto them for safety.

The beach at Parrote, which no longer exists, located where we can presently find La Solana, was a sheltered and appreciated beach, but only women were allowed to go there. Those who would prefer choppier waters would go to Berberiana, currently known as Matadero, Os Pelamios or San Amaro.

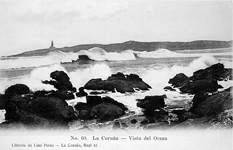

Ruiz Blasco, Picasso's father, had liked A Coruña's sea ever since he had first visited the city. Although his son Pablo never learned to swim, he loved playing in the waves. On several occasions he drew the sea at Orzán and As Lapas. His attention was drawn to a group of women taking a bath dressed with a type of underskirt. He drew them and wrote next to this illustration "this is how women from Betanzos take baths in the sea". This was a habit followed by women coming from inland villages, who used to spend some days in the city in small groups to take their baths in order to rest and improve their health. These swimmers were called catalinas. There is a sculpture honouring them in the Maritime promenade.

The locals' favourite beach was Riazor: it was sheltered, its sand was fine and clean, and there were designated changing room cabins. People were forced to use these since it was forbidden to change clothes outdoors. Riazor offered plenty of services: there were inns, lifeguard boats and ropes that stretched far out into the sea so that swimmers could hold onto them for safety.

The beach at Parrote, which no longer exists, located where we can presently find La Solana, was a sheltered and appreciated beach, but only women were allowed to go there. Those who would prefer choppier waters would go to Berberiana, currently known as Matadero, Os Pelamios or San Amaro.

Ruiz Blasco, Picasso's father, had liked A Coruña's sea ever since he had first visited the city. Although his son Pablo never learned to swim, he loved playing in the waves. On several occasions he drew the sea at Orzán and As Lapas. His attention was drawn to a group of women taking a bath dressed with a type of underskirt. He drew them and wrote next to this illustration "this is how women from Betanzos take baths in the sea". This was a habit followed by women coming from inland villages, who used to spend some days in the city in small groups to take their baths in order to rest and improve their health. These swimmers were called catalinas. There is a sculpture honouring them in the Maritime promenade.

A common leisure activity was going for a walk in Méndez Núñez Park, primarily in Pescadería, in an area which opened to the sea. Before then, there was only San Carlos Park in the old town. The work was carried out thanks to private donations from some wealthy patrons and public underwriting. This park rapidly became an appreciated promenade area. There were rental chairs, a music kiosk, gas-lightning and theatre plays and performances.

Bullfighting was booming at that time, and was encouraged by then Mayor Juan Flórez, who appreciated the touristic appeal these shows brought. A bull ring had just been built in A Coruña with the capacity for holding around ten thousand people. It was located in the present day San Pablo Square until the decade of the 1960s. Like many locals, the Ruiz Picasso family attended some shows at the bull ring just as they used to do in Málaga. Whilst playing with his school friends Picasso liked to pretend he was a bullfighter. Bullfighting was a recurrent topic in his work. His first oil painting, produced in Málaga, depicts a picador.

María Pita and Rosario were some of the celebrations already popular back then. Some other popular celebrations were Santa Margarita and Carnival, when leisure societies held masquerade balls and the entierro de la sardina (a symbolic ritual in which a sardine that symbolises the Carnival is buried in order to get the usual social order re-established), this was usually organised by the Circo de Artesanos.

Leisure societies used to offer a wide range of cultural and spare time activities. Their facilities usually had a reading room, game room, exhibition room, conferences, literary gatherings, recitals, balls and theatrical performances, some of them even had a library and published magazines. There were many of these societies: Reunión Recreativa e Instructiva de Artesanos, Tertulia de La Confianza, Sporting Club Casino Coruñés, Círculo de Gimnasia y Esgrima, Sociedad Bretón de los Herreros, Liceo Artístico, Liceo Brigantino… Some of which still exist today.

A Coruña was famous because of the quality and quantity of its shows. Theatre, zarzuela and opera performances took place frequently in the city, but there were also cafés offering live music, travelling circuses and entertainment stalls.

There were two magnificent buildings very close to each other: the Teatro Principal, currently Teatro Rosalía de Castro, and the no longer existing Circo Coruñés, at the Marina. The former even had its own orchestra and used to hold recitals, theatre performances and balls, whereas the latter would welcome the circus and variety shows.

Picasso's mother was fond of literature and theatre. The family would usually attend the theatre, for the artist once told Olano that they would not miss a single play by José Echegaray, and several of his works were performed in A Coruña while Picasso lived there.

Bullfighting was booming at that time, and was encouraged by then Mayor Juan Flórez, who appreciated the touristic appeal these shows brought. A bull ring had just been built in A Coruña with the capacity for holding around ten thousand people. It was located in the present day San Pablo Square until the decade of the 1960s. Like many locals, the Ruiz Picasso family attended some shows at the bull ring just as they used to do in Málaga. Whilst playing with his school friends Picasso liked to pretend he was a bullfighter. Bullfighting was a recurrent topic in his work. His first oil painting, produced in Málaga, depicts a picador.

María Pita and Rosario were some of the celebrations already popular back then. Some other popular celebrations were Santa Margarita and Carnival, when leisure societies held masquerade balls and the entierro de la sardina (a symbolic ritual in which a sardine that symbolises the Carnival is buried in order to get the usual social order re-established), this was usually organised by the Circo de Artesanos.

Leisure societies used to offer a wide range of cultural and spare time activities. Their facilities usually had a reading room, game room, exhibition room, conferences, literary gatherings, recitals, balls and theatrical performances, some of them even had a library and published magazines. There were many of these societies: Reunión Recreativa e Instructiva de Artesanos, Tertulia de La Confianza, Sporting Club Casino Coruñés, Círculo de Gimnasia y Esgrima, Sociedad Bretón de los Herreros, Liceo Artístico, Liceo Brigantino… Some of which still exist today.

A Coruña was famous because of the quality and quantity of its shows. Theatre, zarzuela and opera performances took place frequently in the city, but there were also cafés offering live music, travelling circuses and entertainment stalls.

There were two magnificent buildings very close to each other: the Teatro Principal, currently Teatro Rosalía de Castro, and the no longer existing Circo Coruñés, at the Marina. The former even had its own orchestra and used to hold recitals, theatre performances and balls, whereas the latter would welcome the circus and variety shows.

Picasso's mother was fond of literature and theatre. The family would usually attend the theatre, for the artist once told Olano that they would not miss a single play by José Echegaray, and several of his works were performed in A Coruña while Picasso lived there.

These forms of entertainment were too expensive for most people, who lacked proper education or enough economic means. Although Moyano's law (1857) enforced compulsory primary education for children aged 6 to 9, in reality, during Picasso's generation, 50% of the men and 72% of the women older than 10 years old were illiterate. In A Coruña only two girls studied with Picasso.

At that time, there were ten municipal primary schools in A Coruña. The high school had just been inaugurated; it was a new and fully-equipped building, whose library contained more than two thousand books, as well as all of the instruments and material necessary for the comprehensive study of disciplines such as Physics, Chemistry and Natural History. Picasso was not likely to have taken advantage of these means. He was not a good student. He preferred drawing caricatures and looking at the sea from the school windows. He was enrolled in the high school his first year in A Coruña. After that year, he studied at the Fine Arts School instead, which was on another floor in the same building.

There was also a well-known private and lay school: Dequidt School, founded by Luis Dequidt, the French consul in the city. The school was on Real Street and then moved to Camino Nuevo.

Poor girls would have to settle for Sunday School, founded by Juana de Vega at the Consulate Residence. Women volunteered to teach reading, writing, counting, and Christian doctrine for free to girls and young women who were working as day labourers or servants. In this sense, Picasso's family was privileged. Although they were not wealthy, they received a regular income and had access to culture. They took out a subscription to the magazine edited and published by Emilia Pardo Bazán, Nuevo Teatro Crítico, which young Picasso read devotedly.

Many newspapers and magazines were published and edited in the city. Besides La Voz de Galicia, founded in 1882, there were other publications such as El Diario de Galicia, El Anunciador, La Mañana, El Telegrama, Revista Gallega, El Criterio: Revista de Instrucción Pública de Galicia or El Eco Musical: Semanario de Literatura y Bellas Artes.

At that time, there were ten municipal primary schools in A Coruña. The high school had just been inaugurated; it was a new and fully-equipped building, whose library contained more than two thousand books, as well as all of the instruments and material necessary for the comprehensive study of disciplines such as Physics, Chemistry and Natural History. Picasso was not likely to have taken advantage of these means. He was not a good student. He preferred drawing caricatures and looking at the sea from the school windows. He was enrolled in the high school his first year in A Coruña. After that year, he studied at the Fine Arts School instead, which was on another floor in the same building.

There was also a well-known private and lay school: Dequidt School, founded by Luis Dequidt, the French consul in the city. The school was on Real Street and then moved to Camino Nuevo.

Poor girls would have to settle for Sunday School, founded by Juana de Vega at the Consulate Residence. Women volunteered to teach reading, writing, counting, and Christian doctrine for free to girls and young women who were working as day labourers or servants. In this sense, Picasso's family was privileged. Although they were not wealthy, they received a regular income and had access to culture. They took out a subscription to the magazine edited and published by Emilia Pardo Bazán, Nuevo Teatro Crítico, which young Picasso read devotedly.

Many newspapers and magazines were published and edited in the city. Besides La Voz de Galicia, founded in 1882, there were other publications such as El Diario de Galicia, El Anunciador, La Mañana, El Telegrama, Revista Gallega, El Criterio: Revista de Instrucción Pública de Galicia or El Eco Musical: Semanario de Literatura y Bellas Artes.